This past December, Education Corp. of America, a large for-profit post-secondary college chain, closed its doors permanently at 70 campuses, leaving more than 15,000 students with tens of thousands of dollars in student loan debt for unfinished courses. Perhaps the worst situation a student borrower can face, sudden school closings have become a flash point for a much larger issue—ballooning student loan debt and elevated delinquency rates.

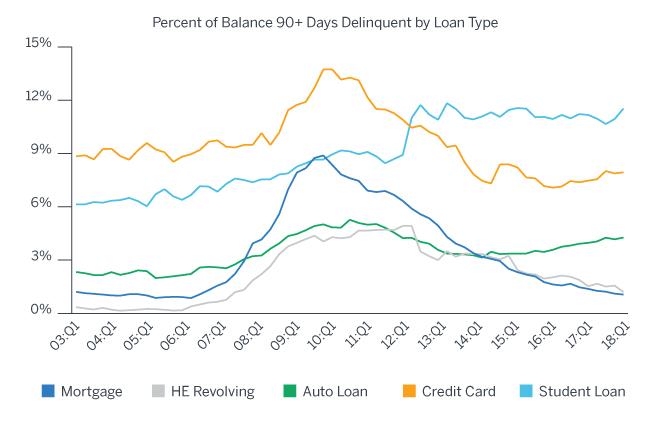

Over the past decade, student loan debt has increased 136%,1 and has maintained a higher level of serious delinquencies in recent years compared to other loan types such as credit card, mortgages, auto loans, and home equity revolving credit.2 Regulation has been created to provide support to student loan borrowers, and a better understanding of the Obama-era rules and the Trump administration's proposals can provide some insight for what may lie ahead.

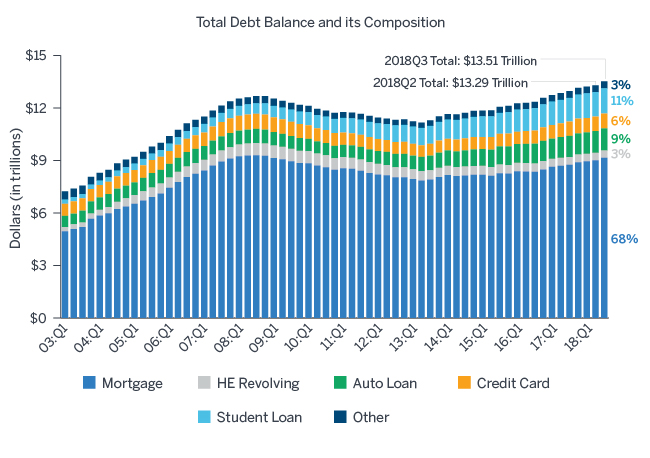

One of the best ways to understand student debt is in the context of overall household debt, which as of September 30, 2018, stood at $13.5 trillion, as seen in Figure 1. This amount is a $219 billion—or 1.6%—increase from the second quarter of 2018. The increase in overall household debt is now 21.2% above the second quarter 2013 trough.

Figure 1: Consumer Debt Total and By Category

Source: Quarterly report on Household Debt and Credit for Q3 2018, New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax.

Student loans, which are at $1.4 trillion, account for 10.7% of overall household debt. While that represents a fraction of the $9.1 trillion in outstanding mortgage balances, student loans nonetheless are the second-largest consumer debt category, overtaking credit card debt and auto loans. A decade ago, student loan debt accounted for less than 5% of household debt.

Increases in the cost of secondary education and the long-term growth in enrollment explain the lion’s share of the triple-digit percentage jump in student loans over the past decade.

The cost component

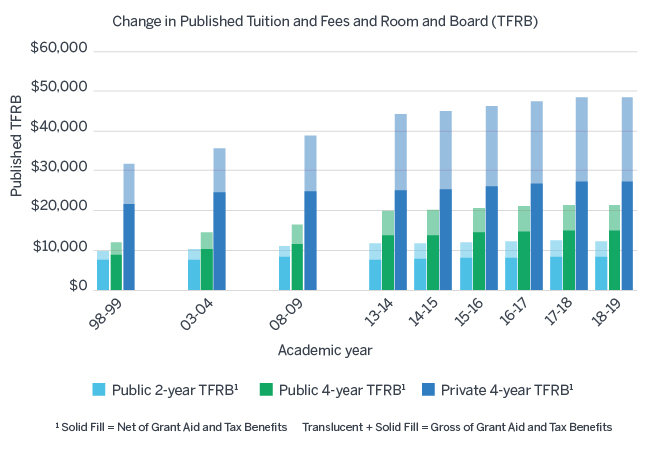

From academic year 2017-18 to 2018-19, the average published tuition and fee costs for full-time in-state students at four-year public colleges and universities rose 2.5% (before adjusting for inflation) to $10,230, according to Trends in College Pricing 2018. The largest increase, at 3.3%, occurred at four-year private nonprofit schools. The smallest increase, at 2.4%, occurred at four-year public out-of-state schools. Similar increases were reported for the overall cost (including room and board) for each school category.

Over the past 10 years, the one-year change in published costs for tuition and fees has moderated, at first hovering in the low single digits for each school category and then flattening further in recent years. This moderation is a change from over a decade ago, when one-year increases between 4.5% and 10.3% were far more common.3 Figure 2 shows the changes in both gross and net published tuition, fees, and room and board since the 1998-99 school year.

Figure 2: Change in College Pricing Over Time

Source: Trends in College Pricing, 2018.

Like list prices for cars, these published prices represent the sticker cost of higher education rather than students’ actual payments, which can be much lower depending on the applicability of tax credits, grants, and other financial assistance. For example, the average in-state net tuition and fee costs at public four-year institutions for the 2018-19 school year was $3,740, slightly more than one-third of the published cost of $10,230.4 At two-year public colleges, the average amount of grant aid and federal education tax credits and deductions for full-time students was about $4,050 in 2018-19, $390 more than needed to cover tuition and fees.5

Between 2013-14 and 2018-19, financial aid has continued to grow in both public and private four-year institutions. Despite this growth, over the past five years, increases in grant aid, tax credits, and deductions for full-time students have fallen short of the increases in tuition and fees. In 2018-19, this assistance covered approximately 45% of the $640 increase (in 2018 dollars) in published tuition and fees at four-year public colleges and universities and approximately 63% of the $3,330 increase in published tuition and fees at four-year private nonprofit schools.6

Financial assistance can affect colleges’ and universities’ prices. For example, costs at public institutions tend to rise faster as state and local funding per student slows or declines.7

A clouded enrollment picture

Student loans are also a function of enrollment, which grew from 15.3 million students in 2000 to 20.8 million in 2010, a nearly 37% increase. However, starting in 2010, this seemingly relentless growth stalled, with enrollment falling to 19.7 million over the next six years, a 5.6% decrease. The entire decrease for this six-year period can be traced to both two-year public colleges and for-profit schools, which saw a decrease in enrollment of 12% and 42%, respectively. In the other sectors, enrollment continued to grow between 5.9% and 6.2%.8

In the aftermath of hundreds of for-profit school closings, including such high profile names as Corinthian Colleges and ITT Technical Institutes, for-profit schools have found attracting students to be an uphill battle. Stiff competition from nonprofit private and public schools has also taken its toll on enrollment.

A relative blip on the radar screen when compared with the enormous growth in the early 2000s, this decrease in enrollment seems to have had little impact on the overall level of outstanding student loan debt.

Between 2016 and 2027, total undergraduate enrollment is projected to rise a modest 3.0%.9

And while enrollment and college and university costs weigh heavily on the level of student debt, other factors such as grants and financial aid, changes in family income, regulation changes, and the overall economy, among others, also play into the student loan equation.

A squishy number

Rising levels of student debt, however, are not nearly as important a question as delinquencies, which, though moderating somewhat, are elevated. In fact, starting in 2012 the delinquency rate for student loans topped those for auto, credit card, and mortgages, as seen in Figure 3. Over the past decade, the delinquency rate for student loans 90 or more days delinquent has climbed from 7.6% to 11.5% as of the third quarter of 2018, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Figure 3: Delinquency Rate by Loan Type

Source: Trends in College Pricing, 2018.

As alarming as this 11.5% rate of delinquency is, it could be an underestimate of the actual rate of delinquency. This is because about half of outstanding loans are currently in deferment, grace periods, or forbearance. Federally backed loans, which represent the vast majority of student borrowing, can be deferred until the student graduates, and even then payment can be deferred another six months. These loans are, therefore, not included in the repayment cycle, but are included in the total balance of outstanding student loans.10 From a mathematical standpoint, the loans in some form of deferment are included in the denominator of the delinquency rate calculation, but because they are not in the repayment cycle, they are not included in the numerator.

A large portion of delinquencies can be traced to borrowing in order to finance an education at for-profit schools. Students at these schools account for approximately 11% of the post-secondary education population but 44% of all federal student loan defaults.11

Equally hard to ignore is the fact that for-profit schools cost four times as much as community colleges. More than 80% of students attending for-profit schools borrow to pay for their education compared with less than half of students at public institutions.12

Two views of a way forward

For-profit schools came under scrutiny by the Obama administration, which signed legislation aimed at protecting students from “large amounts of debt” incurred while attending schools that provided “poor quality training, often for low-wage jobs” or occupations with limited job opportunities.

Two pillars of Obama-era reforms are the borrower defense and the gainful employment rules, which apply to career-training programs offered at private nonprofit and public institutions, as well as for-profit schools.

Originating in 1995, the borrower defense rule had not been widely used as a relief mechanism in the student loan market until 2015, when it was revised to include additional guidelines for claims against schools. Among these provisions, the rule:

- Forgives federal loan obligations if borrowers can show they were defrauded under state law

- Includes a Pay As You Earn program that limits a borrower’s payments to 10% of discretionary income and forgives the balance after 20 years

- Bans mandatory arbitration clauses in enrollment agreements

The U.S. Department of Education (DOE) under the Obama administration also implemented a closed school forgiveness program that automatically forgives federal student loan obligations if the school closed while a student was enrolled or shortly after attending it and the student did not transfer the credits to another school.

The Inner Workings of Gainful Employment

Under the gainful employment rule, certificate and training programs are graded based on debt-to-income requirements. Schools:

- Pass if graduates’ annual loan payments are less than 8% of total earnings or 20% of discretionary earnings

- Are flagged as “in the warning zone” if graduates’ loan payments are between 8% and 12% of total earnings or between 20% and 30% of discretionary earnings

- Fail if graduates’ loan payments are greater than 12% of total earnings and greater than 30% of discretionary earnings

Schools would become ineligible for federal student aid if the program failed in two of three consecutive years or were in the warning zone for four consecutive years.

Source: Mayotte, B. (July 8, 2015), What the new gainful employment rule means for college students, U.S. News & World Report.

A companion to the borrower defense rule, the gainful employment rule requires career-training programs to meet minimum debt-to-earnings thresholds. (See the sidebar "Inner Workings of Gainful Employment.") Programs that result in this ratio becoming too large would be at risk of losing their access to federal student aid programs.

Also seeking increased accountability in post-secondary education, the Trump administration would like to see a more market-based approach to reforming student loan debt. Rather than targeting schools on their tax status, the Trump DOE seeks to make the system more transparent by providing more meaningful information that students can use in selecting a school across the entire higher education spectrum. It also emphasizes personal accountability for the decisions students make.13

For example, as an alternative to the gainful employment rule, the DOE proposes to increase the information provided by the College Scorecard or on schools’ websites to include a program’s completion rates, total costs, accreditation, and compliance with state licensure requirements. This approach would free up an additional $5.3 billion to fund programs at schools that are in jeopardy of losing access to student financing under the gainful employment rule, according to the department’s estimate.14

In August 2018, the DOE invited comments on the merits of disclosing this type of information on a school’s website, but subsequently missed a November deadline to issue a final rule for 2019, delaying the implementation of any revised rules.

Concerned that taxpayers would have to pick up too much of the tab under the Obama-era borrower defense rules, the DOE has also proposed stricter standards for loan forgiveness that require students to prove that schools knowingly deceived them. Revisions to the Obama-era student loan forgiveness programs would save taxpayers $12.7 billion over 10 years, according to the DOE's estimate.15

In October, a lawsuit related to arbitration clauses and provisions for students to file their claims jointly was rejected by a federal judge, who ruled that the DOE’s delay in enforcing Obama-era rules was unlawful.

The DOE said it accepted the court’s decision and in December canceled $150 million in student loans under the closed school forgiveness program. The loan forgiveness applies to approximately 15,000 borrowers, about half of whom attended Corinthian Colleges.16

Approximately 139,000 applications have been filed with the DOE under the borrower defense rule since 2015. Of these, 99,000 are pending, according to data released by Sen. Dick Durbin in May 2018.17

Other proposals by the Trump administration and Republican Party (GOP) legislators to combine repayment options and merge federal loan programs into a single program could help simplify student loan borrowing for individuals, but would likely not affect total student debt levels.

Another GOP proposal would require students, while still attending school, to pay interest on their outstanding loans, thereby ending subsidized loans for students. Ending this subsidization would likely increase delinquency rates or delay graduation for cash-strapped students who are unable to meet their obligations. It is important to note that these efforts are still evolving pieces of legislation and are subject to change as they move through the legislative process.

The Obama-era rules will likely continue to guide the student loan environment for the near future, given the aforementioned court ruling and the Trump administration’s acceptance of this decision. If student claims are processed under Obama-era programs, delinquencies would be expected to decline somewhat. And as the Trump administration’s proposals take effect and more meaningful information about school programs reaches student borrowers, it would be expected that, over time, students would be able to make better choices about their education, which could improve their job prospects and the likelihood that loans will be repaid. Over time, the student loan delinquency rate could improve. But regulations and legislation do not happen in a vacuum. Any one of a variety of forces, from consumer behavior to the economy to changes in family income, could drastically alter the path forward.

1 Calculations based on the quarterly report on Household Debt and Credit for Q3 2018, published by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Retrieved February 13, 2019, from https://www.newyorkfed.org/microeconomics/hhdc.html.

2Q3 2018 Household Debt and Credit Report, ibid. p. 12.

3The College Board. Trends in College Pricing 2018, Table 2, p. 12. Retrieved February 13, 2019, from https://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/2018-trends-in-college-pricing.pdf.

4Trends in College Pricing 2018, ibid, p. 18.

5Trends in College Pricing 2018, ibid, p. 17.

6Trends in College Pricing 2018, ibid, p. 18-19. Calculations by the author.

7The College Board. Trends in College Pricing 2017, p. 8. Retrieved on February 13, 2019, from https://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/2017-trends-in-college-pricing_0.pdf.

8Trends in College Pricing 2018, op cit., p. 30.

9National Center for Education Statistics (2018). The Condition of Education, p. 158. Retrieved February 13, 2019, from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/.

10Brown, M., Haughwout, A., Lee, D. et al. (March 5, 2012). Grading Student Loans. Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Retrieved February 13, 2019, from https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2012/03/grading-student-loans.html.

11DOE (October 30, 2014). Obama administration announces final rules to protect students from poor-performing career college programs. News release. Retrieved February 13, 2019, from https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/obama-administration-announces-final-rules-protect-students-poor-performing-career-college-programs.

12DOE (October 30, 2014), ibid.

13DOE (August 10, 2018). U.S. Department of Education proposes overhaul of gainful employment regulations. News release. Retrieved February 13, 2019, from https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/us-department-education-proposes-overhaul-gainful-employment-regulations.

14Kreighbaum, A. (August 13, 2018). For-profits keep access to billions in aid. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved February 13, 2019, from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/08/13/dropping-gainful-employment-means-profits-keep-billions-student-aid.

16Cowley, S. (December 14, 2018). Education Dept. will cancel $150 million in student debt after judge’s order. New York Times. Retrieved February 13, 2019, from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/14/business/student-loan-debt-forgiveness.html.

17Meckler, L. & Douglas-Gabriel, D. (July 25, 2018). Trump administration moves to make it harder for defrauded students to erase debt. Washington Post. Retrieved February 13, 2019, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/grade-point/wp/2018/07/25/trump-administration-moves-to-make-it-harder-for-defrauded-students-to-erase-debt/?utm_term=.7fba5cffc098.